At a service at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance this week, Shrine Governor Commander Terry Makings AM laid a wreath commemorating the sinking of HMAS destroyer Vampire almost three quarters of a century ago.

Whilst escorting the British light aircraft carrier Hermes (itself lost in the same action), the Vampire was sunk on April 9, 1942 by a Japanese bomber of the coast of Ceylon.

On board the Vampire was Ernie Pilkington. The previous year, Ernie had a run with Carlton.

When Ernie first fronted as a hopeful at Princes Oval, he’d already answered a nation’s calling that able-bodied young men could serve a greater purpose as fighters, not footballers. It was 1941, and an entry lodged in the Carlton Football Club’s annual report later that year noted the club’s struggle for numbers, which “may be explained by the enlistments and call-up for military training of many of the best players".

“[These] players, whose names were retained on the training list during the past three years, have answered the country’s call by volunteering for service overseas. They are serving in various parts of the world and we are happy to say that latest information tells of their safety. We also know that, whatever their duty, whatever their task, they will meet them bravely.”

Signalman Ernest Richard Pilkington, service number H/1030, was already on temporary leave when he fronted for training at Carlton. Born and raised in Hobart, Ernie was 13 days short of his 21st birthday when, on September 2, 1939 he first reported for duty for the Royal Australian Navy.

At Carlton, Ernie never got the football call-up he so desperately craved. In any event, there was a war to win and, having earlier served on the Cerberus and later the Derwent, Adelaide and Penguin, Ernie was soon assigned to the HMAS Vampire, which was operating from Colombo as part of the Eastern Fleet. On March 1, 1942, Colombo was half a world away from Carlton.

Ernie could not have known of the catastrophe that awaited when the Vampire and Hermes, was attacked off Batticaloa. The Hermes was hit first at 10.35 and, according to one account, went down within 20 minutes “with one four-inch gun still firing”. The Vampire, which managed to shoot at least one enemy aircraft out of the sky, was then struck by a bomb which broke her in half. She joined Hermes beneath the sea barely 30 minutes later.

Nineteen officers and 288 ratings of the Hermes, plus the Commanding Officer and eight ratings of the Vampire, were lost or died of wounds. Some 600 were rescued by the British hospital ship Vita, while others were picked up by local craft and a few swam ashore.

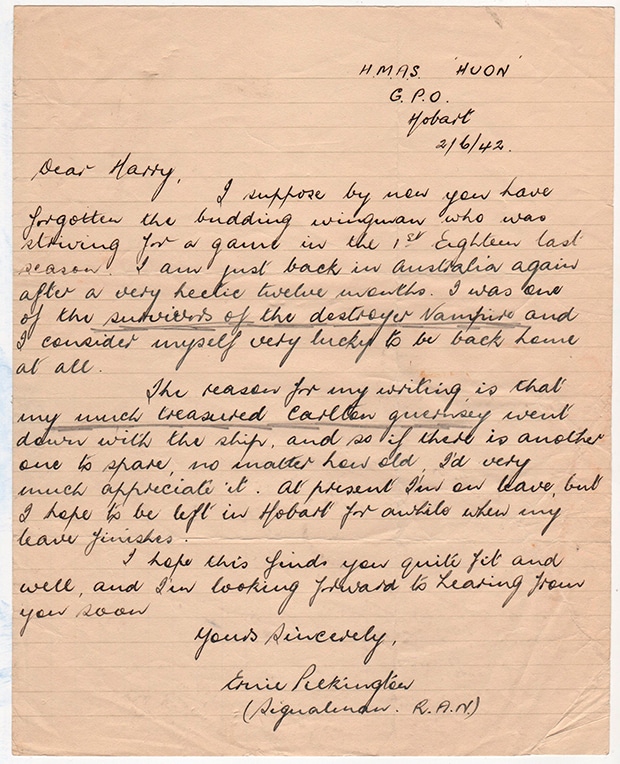

Ernie somehow survived, but the events of April 9 later prompted him to pen the following letter to the former Carlton footballer and then Club Secretary Harry Bell.

H.M.A.S. ‘Huon’

G.P.O. Hobart

2/6/42

Dear Harry,

I suppose by now you have forgotten the budding wingman who was striving for a game in the 1st Eighteen last season. I am just back in Australia again after a very hectic twelve months. I was one of the survivors of the destroyer Vampire and I consider myself very lucky to be back home at all.

The reason for my writing is that my much treasured Carlton guernsey went down with the ship, and so if there is another one to spare, no matter how old, I’d very much appreciate it. At present I’m on leave, but I hope to be left in Hobart for a while when my leave finishes.

I hope this finds you quite fit and well, and I’m looking forward to hearing from you soon.

Yours sincerely,

Ernie Pilkington

(Signalman, R.A.N.)

The Pilkington letter.

Ernie Pilkington never got the chance to represent the Carlton Football Club at senior level, yet his military record was something to be proud of. Ernie’s records reveal that, after surviving the sinking of the Vampire and taking his well-earned leave, he continued to serve as a wartime signalman aboard such vessels as the Moreton, Magnetic, Platypus, Dubbo, Bowen, and finally, Huon, until he was demobilized on February 12, 1946.

Ernie also made a sizeable mark on the post-war local Tasmanian football competition. A good mate, Ken Anderson, drew on his extensive knowledge of the local game to confirm that Ernie represented the now-defunct Sandy Bay and was named in the club’s all-time best 25. Ernie also was a member of Sandy Bay’s first premiership team of 1946 (coincidentally captained and coached by Lance Collins, who had put his body on the line for the Blues in “The Bloodbath” Grand Final the previous year) and had taken out the William Leitch Medal for the competition’s best and fairest.

Pilkington’s links with Sandy Bay ended in 1951. As the Seagulls’ historical record, The Spirit Never Dies, reported; “At the end of the season Ernie Pilkington, who had played 99 games with the club, announced his retirement from senior football as he intended seeking a coaching position. He was eventually appointed to the Tunnack Club in the Midlands Association, and despite overtures from the club to take part in the first match in 1952 to enable him to qualify for Player’s Life Membership he felt it his duty to appear in new colours. Pen and paper will never be able to adequately do justice to this great player, but let it be said that Ernie was one of the finest players this state has seen.”

It is left to Ernie’s son Leigh to tell the story of a life well lived. “Ernie died in Hobart in 2004. He was 86 and he had a good life, like most of those blokes who came back from the war. For the next 20 or 30 years they tried to catch up on all those years they lost during wartime,” Leigh said recently.

“Ernie trained as a signalman in Tasmania then went off to war pretty early, and one of his early major postings was aboard the Vampire. One of his old shipmates actually found an aerial photograph in the Japanese archives of the aircraft carrier Hermes on the way down and the Vampire just before she got knocked down too.

“Ernie got picked up (after the Vampire was bombed) and he spent quite a while in the water, like so many of them. He got out of it all right but a bit later on he had a few health problems. He had a fair bit of intestinal trouble due to the bombs going off in the water but he was certainly well active into his 70s. He never really dwelt on all that though – he preferred to talk more about his footy days because they were good days for him.

“He talked about the football games they organised during wartime. He played in a few combined footy games during the war – you know, Victoria versus the rest – whenever the shipmates were in Australia on their days off.”

Ernie’s touching letter to Harry Bell was a complete revelation to his son, who couldn’t say whether a replacement guernsey ever came his father’s way. Leigh didn’t even know that his dear old Dad boarded the Vampire with his precious Navy Blue artefact, and that the old guernsey went down with the ship.

“In those days you would take a few personal items with you, but he never mentioned anything,” he said.

“I do remember him mentioning the time he trained at Carlton and then it was back off to war. He used to talk about being based down at Frankston and having to ride up to training at Carlton and back again on a motor bike. Dad followed Carlton and always had a soft spot for the Blues, and in later years he went back to see them play in a few finals.”