THE BEST wingman in southern Tasmania was aboard the naval destroyer HMAS Vampire when the Japanese attacked from the air.

It was April 9, 1942, and the Vampire was cruising with the British light aircraft carrier HMAS Hermes off the east coast of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka.

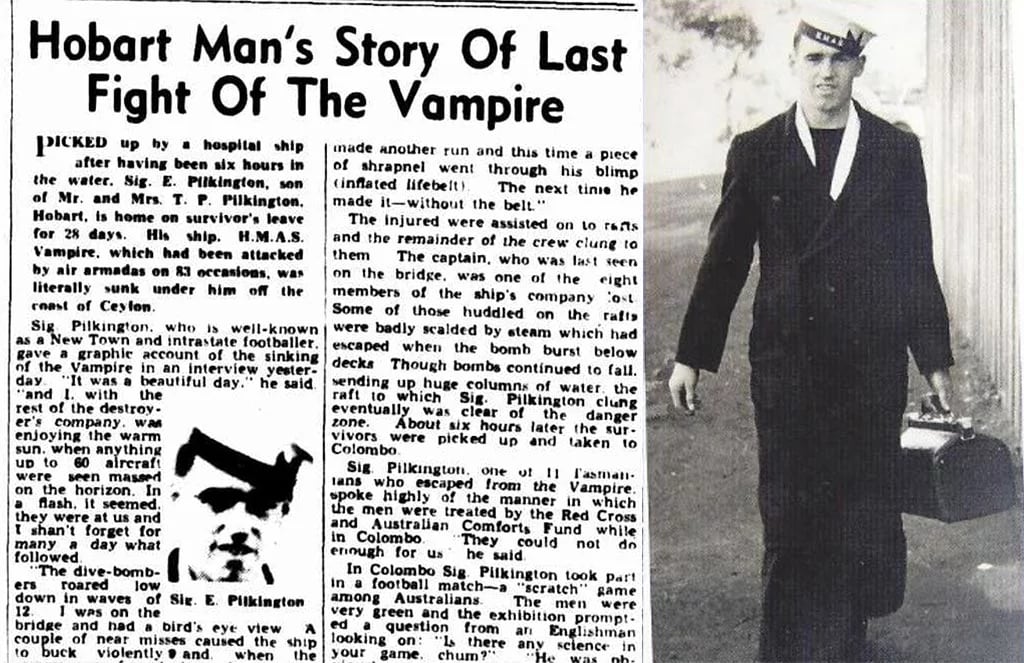

"It was a beautiful day," Ernie Pilkington would later tell Hobart newspaper The Mercury as he convalesced on survivors' leave.

"I, with the rest of the destroyer's company, was enjoying the warm sun when anything up to 60 aircraft were seen massed on the horizon. In a flash, it seemed, they were at us …"

The best stab pass in Tasmania

Before joining the Royal Australian Navy shortly after his 21st birthday and reporting for duty on September 2, 1939 – the day after Germany invaded Poland – Pilkington earned local fame as a footballer.

The talented youngster graduated to senior football with Tasmanian Football League club New Town, coached by legendary ruckman Roy Cazaly, in 1936. Then 17, Pilkington broke into the reigning premiership team and after just three games he was selected to represent the South of the state against the North.

A gifted wingman, he would come to be regarded as "probably the best stab pass" in the entire state.

Ernie Pilkington, far right, was considered the best stab pass in Tasmania. Picture: Sandy Bay & South East Past Players, Officials and Supporters' Association

While stationed at Flinders naval base on Victoria's Mornington Peninsula in February 1941, Pilkington pursued big league football with Carlton, travelling the 180km round trip to and from training on a motorbike.

A well-proportioned 172cm, Pilkington was handed the No. 36 guernsey and excelled in a practice match between the recruits of Carlton and Fitzroy. He played in the seconds but was unable to break through for a senior game in a team that would be minor premiers.

In any case, he was to be dragged away by service commitments.

After becoming a signalman and serving on several ships, Pilkington married Edie Johnston in Hobart on September 5, 1940. The newlyweds honeymooned in Melbourne, after which Edie went back to Hobart. Pilkington returned to naval duty and a year later found himself aboard the Vampire.

Devastation in Bomb Alley

A perilous October, 1941 journey from Java to Singapore took the destroyer through an ominous stretch nicknamed "Bomb Alley", and at dawn they were informed floating mines were ahead. They managed to weave their way through and emerge unscathed, but wouldn't have been so fortunate had they passed through a little earlier in darkness.

The destroyer HMAS Vampire. Picture: Allan C. Green, State Library of Victoria

On December 10, 1941 – just three days after the Japanese attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbor – Pilkington witnessed the devastating bombing and sinking of two British battleships, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, in the South China Sea.

In a letter to his family, Pilkington described the horror:

I was there and saw the lot. It was a horrible sight…

We were so proud of the big ships, and thought they could go through anything. Nearly 60 torpedo bombers attacked together, and I'm certainly glad I'm on a small ship. We fly round, zig-zagging, and can dodge anything.

They let go at us. We brought down nearly a dozen of them, and it's a great sight to see them crash into the sea and blow up.

The worst part of the whole lot was picking up survivors. They were as cheerful as anything. The water was almost as thick as mud with fuel oil and lots of the poor devils had swallowed pints of it.

We gave them everything we had – cigarettes, food, clothes. I helped to pull in a commander, and we gave him a cup of tea in a filthy cup which everyone had drank from. He loved it.

There were (Japanese) aeroplanes overhead while we were picking up the lads, but they did not bother us, so that's one thing in their favour.

Saved by a football

Five months later, Pilkington and his Vampire colleagues would suffer a similar fate. After surviving 83 air raids the mighty warship had built an air of invincibility, but she would prove fallible in devastating fashion.

"The (Japanese) dive-bombers roared low down in waves of 12," Pilkington would tell The Mercury.

“I was on the bridge and had a bird's-eye-view. A couple of near-misses caused the ship to buck violently, and when the screws were forced clear she shivered from stem to stern.

"Those fellas dive perpendicularly down to about 150-200 feet (45-60 metres), and it was all over when one struck us midship. The Vampire broke in half and, before we knew it, we were in the water."

The Hermes sank in 20 minutes. The Vampire took 30.

The destroyer had been destroyed, and so had the lives of more than 300 Australians.

Pilkington was not among them, he later told Blues officials, only because "by clinging to an inflated football for some time in the water he was able to save his life".

As a headline in The Australasian put it: 'ONE OF CARLTON'S PLAYERS ON SERVICE SAVED BY A FOOTBALL'.

He grabbed his footy before he went over the side.

So far as is known, the quick-thinking 23-year-old never mentioned this detail to a journalist, but his only surviving son insists it's true.

"I heard Dad talk about it enough times, and some of his old cronies – who are long gone now – reiterated that story about the football," Leigh Pilkington told AFL.com.au.

"Dad was in the bridge and all his stuff was up there, including his footy because they'd have a kick and play footy matches whenever they could.

"He grabbed his footy before he went over the side because it was the first thing he could think of that might be useful in the water. And it was.

"If he didn't love football so much, maybe things might've turned out a bit different. I mightn't be here."

Pilkington, right, cuts a dashing figure in his navy gear (Picture: Leigh Pilkington). Left, the report of his amazing escape in Hobart's Mercury

After clinging to his football and a wooden raft for six hours in the sea, Pilkington and more than 600 others were rescued by a British hospital ship and other local boats and taken to Colombo, Ceylon's capital.

Nothing is known of Pilkington's life-saving football – not its brand nor its eventual fate.

"I reckon it got forgotten when they were getting rescued," Leigh Pilkington said.

I saved a football but I didn't save my Carlton jumper

Ernie suffered blast injury, and in that respect was luckier than many of his colleagues.

It wasn't long before he was well enough to play a football 'scratch match' in Colombo. The curious clash prompted an English spectator to ask the knockabout signalman: "ls there any science to your game, chum?"

"He was obviously a soccer player," Pilkington told The Mercury.

When he returned to Hobart, Pilkington finally met his eight-month-old son Glann, whom he had named after a navy mate. "That was worth everything we went through and more," the proud father said. (Glann died in a car accident in the 1970s.)

Despite being lucky to escape with his life, Pilkington still harboured a regret. He'd been so proud of the Carlton guernsey the club had given him that he'd taken it with him on service, and he was disappointed when it went down with the Vampire.

"Dad said, 'I saved a football but I didn't save my Carlton jumper'," Leigh Pilkington said.

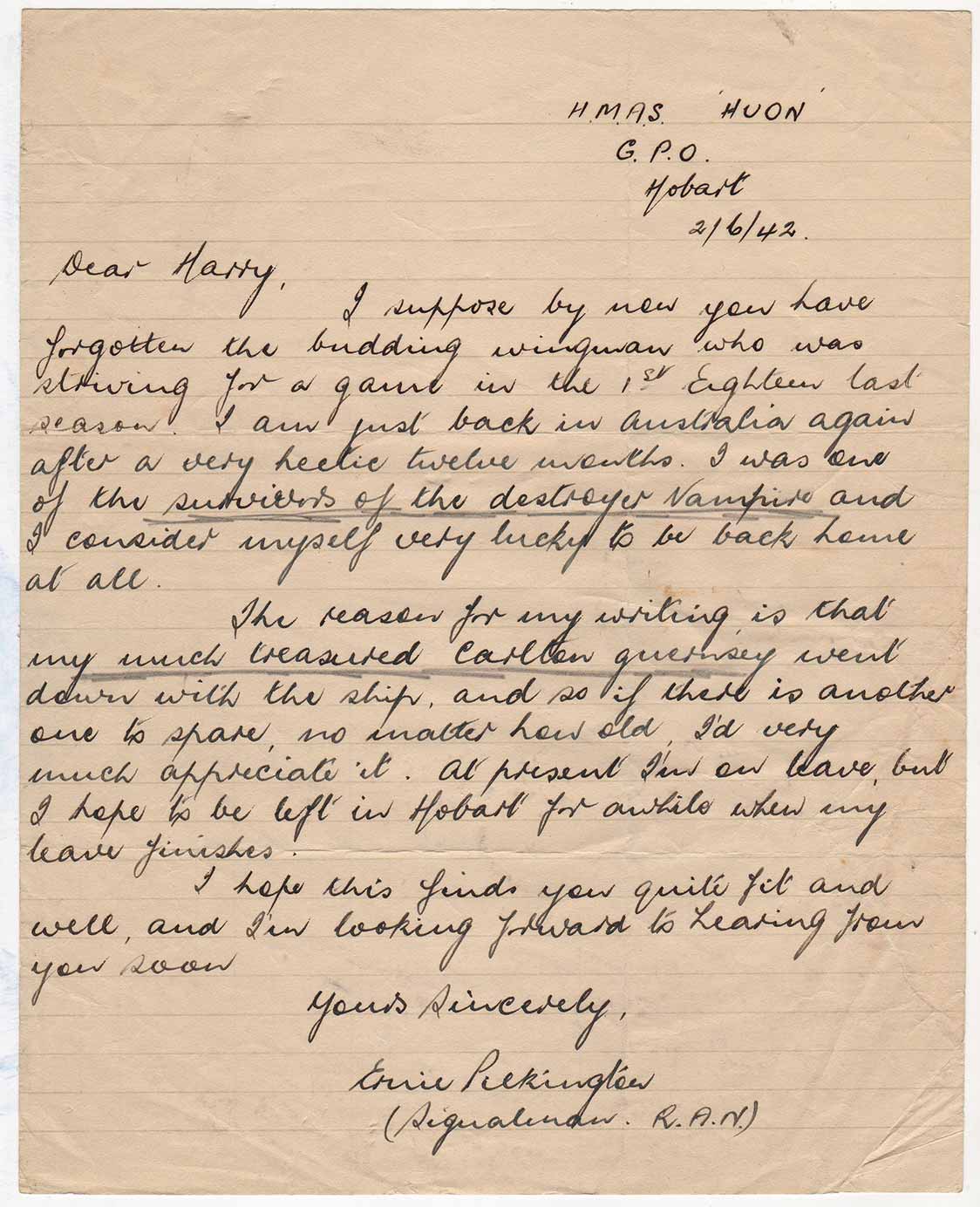

Within two months of the sinking, Pilkington wrote to Blues secretary Harry Bell to ask for a replacement guernsey.

The following letter was found in the Blues' archives 2015 by Carlton historian Tony De Bolfo, who wrote about Pilkington for the club website.

H.M.A.S. 'Huon'

G.P.O. Hobart

2/6/42

Dear Harry,

I suppose by now you have forgotten the budding wingman who was striving for a game in the 1st Eighteen last season. I am just back in Australia again after a very hectic twelve months. I was one of the survivors of the destroyer Vampire and I consider myself very lucky to be back home at all.

The reason for my writing is that my much treasured Carlton guernsey went down with the ship, and so if there is another one to spare, no matter how old, I’d very much appreciate it. At present I’m on leave, but I hope to be left in Hobart for a while when my leave finishes.

I hope this finds you quite fit and well, and I’m looking forward to hearing from you soon.

Yours sincerely,

Ernie Pilkington

(Signalman, R.A.N.)

Pilkington's hand-written letter to the Blues requesting a replacement guernsey. Picture: Carlton Media

Leigh Pilkington doesn't believe the Blues came to the party, but he accepts anything is possible given he only found out about his late father's letter when it surfaced four years ago.

If your old man hadn't been such a good signalman he'd have spent half the war in bloody jail.

For Ernie there were more pressing issues at the time, such as survival.

"Dad said that early in the war they weren't frightened because they thought they were going to lose the war anyway and nothing they did was going to make a difference. But when the tide turned, they thought, 'We'd better be a bit careful here so we can have a life after the war,'" Leigh Pilkington said.

Signalman Pilkington served on 13 ships, some of them multiple times, and his service record rated his character as "very good" and his efficiency as "satisfactory".

Pilkington loved talking about the mischief he and his mates made while away, with a navy colleague later telling Leigh: "If your old man hadn't been such a good signalman he'd have spent half the war in bloody jail."

Leigh Pilkington elaborates: "Dad might've been told he wasn't allowed to play footy because the ship was leaving the next day but he'd do it anyway. The captain would give him a dressing down and say, 'We'll deal with this later!'"

A Tassie club great

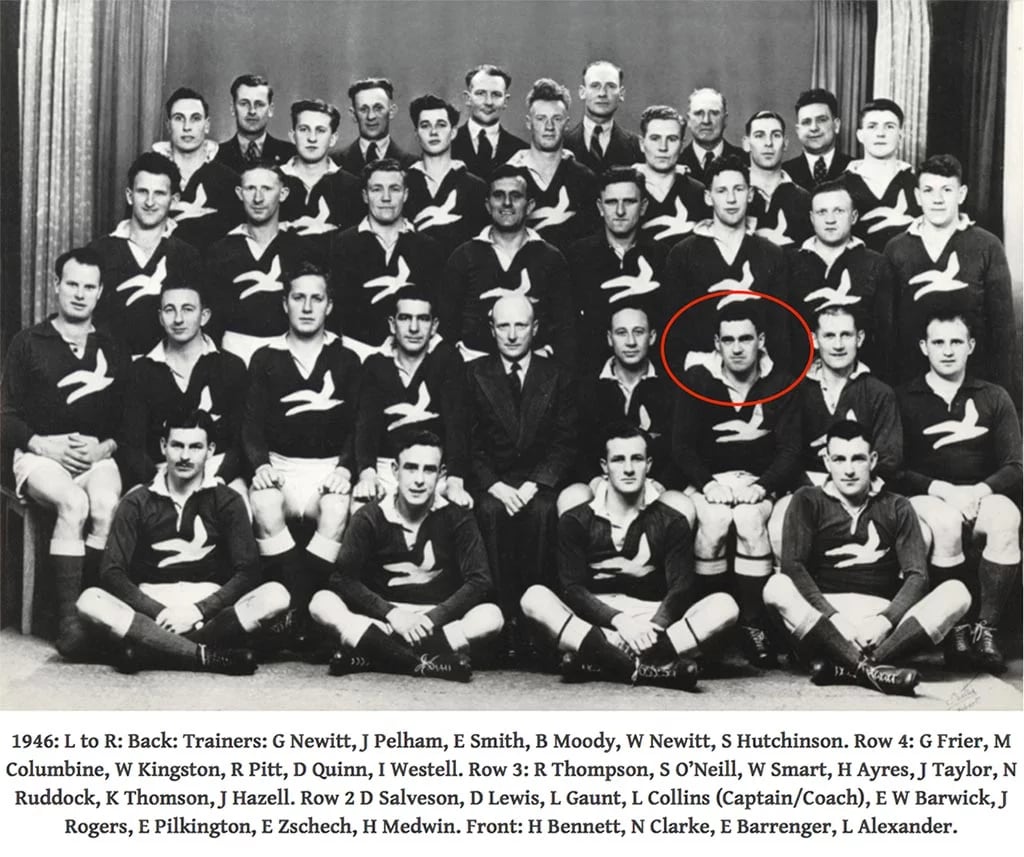

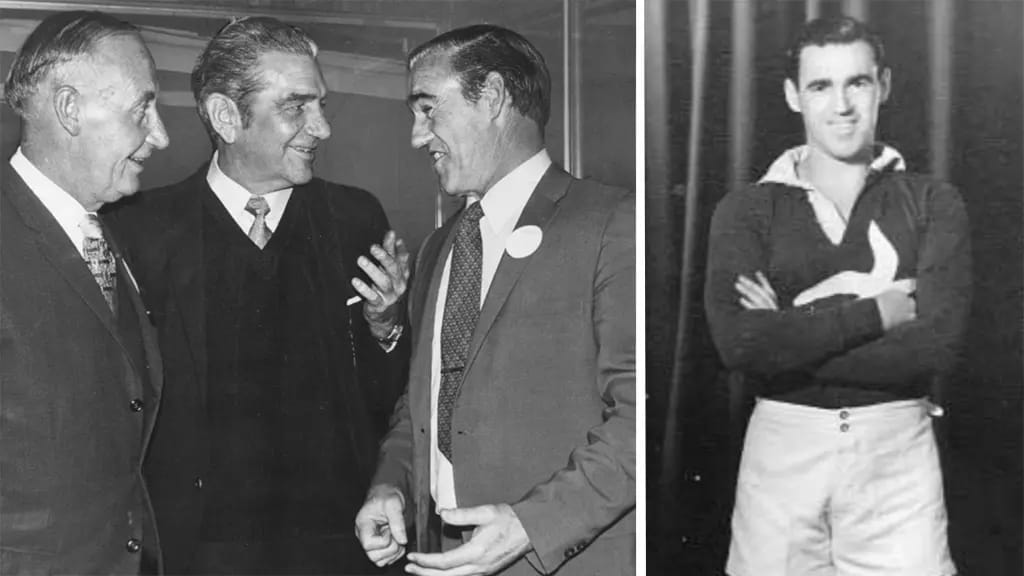

Pilkington relished a return to top-level football in Hobart after the war, joining the new Sandy Bay club in 1946, when he won the League's William Leitch Medal, the club best and fairest and best-afield honours in the club's first premiership side, coached by Carlton's premiership forward Lance Collins.

Pilkington (circled) was considered one of Sandy Bay's greatest players. Picture: Sandy Bay & South East Past Players, Officials and Supporters' Association

Pilkington represented Tasmania in the 1947 carnival in Hobart, captain-coached Sandy Bay in 1948-49 and captained the South representative team in 1950.

Later adjudged one of the greatest 25 players in the history of the now-defunct Sandy Bay, he then coached Tunnack to a first-up premiership in 1952 but broke his ankle the next year and retired.

Pilkington remained active in retirement, taking up golf with enthusiasm.

"Dad was like a lot of young blokes who missed out on six years of life because of the war – when they got back they were always trying to make up for lost time," his son said.

But Pilkington still suffered the effects of the bombing and sinking of the Vampire.

In ill health late in his life, he was unsuccessful in his application to be classified as a Totally and Permanently Incapacitated ex-servicemen.

An old mate tried to help his cause, visiting Japan's national archives, where he found an aerial photo of the attack on the Vampire and the Hermes. When he returned to Hobart, he gave Pilkington a copy of the photo and said, "Take that to your doctor and see if he reckons you're entitled to TPI."

Left: Pilkington (r) chats to Carlton premiership forward Lance Collins (c). Right: in his playing days for Sandy Bay. Pictures: Sandy Bay & South East Past Players, Officials and Supporters' Association

Pilkington died in 2004, aged 86. To the end he had a special place in his heart for the Blues, for football in general, and for the one football in particular that had helped save his life.

"How could you not love football after hearing a story like that?" Leigh Pilkington said.